Rudolf Steiner and the Threefold Forces in Our Time

Loosening Ahriman's Grip

Imagine you’re at a crossroads. One path leads up toward dreams, creativity, and spiritual freedom. Another descends down toward logic, technology, and machines. Between them runs a third path that blends both, using love and wisdom to balance the extremes. Which path are you on right now, and how do you know?

This metaphor captures how Rudolf Steiner (1861–1925) saw the human journey. Founder of the spiritual science he called Anthroposophy,1 Steiner taught that three main forces shape history, culture, and our inner lives: Lucifer, Ahriman, and the Christ being. He believed we can live better if we can learn to notice these forces in ourselves and keep them balanced.

The Three Forces

Lucifer’s Creative Spark

From the Latin lux (light) and ferre (to bring), Lucifer is the “light-bringer.” For Steiner, this force draws us toward imagination, excitement, and daring ideas. It fuels art, music, visionary founders, and the sense that the universe is alive with meaning.

Steiner said Lucifer’s peak influence was during the “Age of Myth” (prehistory to around 500 BCE), when societies were guided mostly by myth, ritual, and inner spiritual wisdom. Yet, too much of Lucifer’s influence leads to us drifting away from practical reality, and we risk floating off into fantasy and egoism, losing touch with day-to-day life.

Ahriman’s Cold Logic

In contrast, Ahriman (derived by Steiner from the ancient Persian figure Angra Mainyu)2 drags us the other way toward material things: facts, machines, rules, and strict order. Since about 1500 CE, the “Age of Mechanism,” Ahriman’s influence has grown with science, industry, bureaucracy, and now, AI.

This force isn’t simply “bad.” We need it because it compels us to think clearly, build useful tools, and get sh*t done. However, too much Ahriman leaves life cold and rigid. Efficiency, metrics, formulas, and technology overshadow meaning and human warmth.

As Steiner warned in 1919, Ahriman is “infinitely clever,” driving technological advance faster than our moral nature can keep pace:

“In our present age, Ahriman is a greater threat to us than Lucifer. He is infinitely clever and is helping us to develop our technological civilisation. He wishes us to advance at breakneck speed, long before our individuality and moral nature are ready for such advances... The scientist, the technologist and the inventor are Ahriman’s natural prey but all of us can fall victim to his temptations.”3

Christ’s Integration

Between these extremes is the Christ being. For Steiner, Christ isn’t just the historical Jesus but a living force of balance and compassion. Emerging during “The Age of the Soul” (~500 BCE to ~1500 CE), this impusle bridges Eastern mysticism and Western pragmatism, bringing balance and new kinds of awareness.

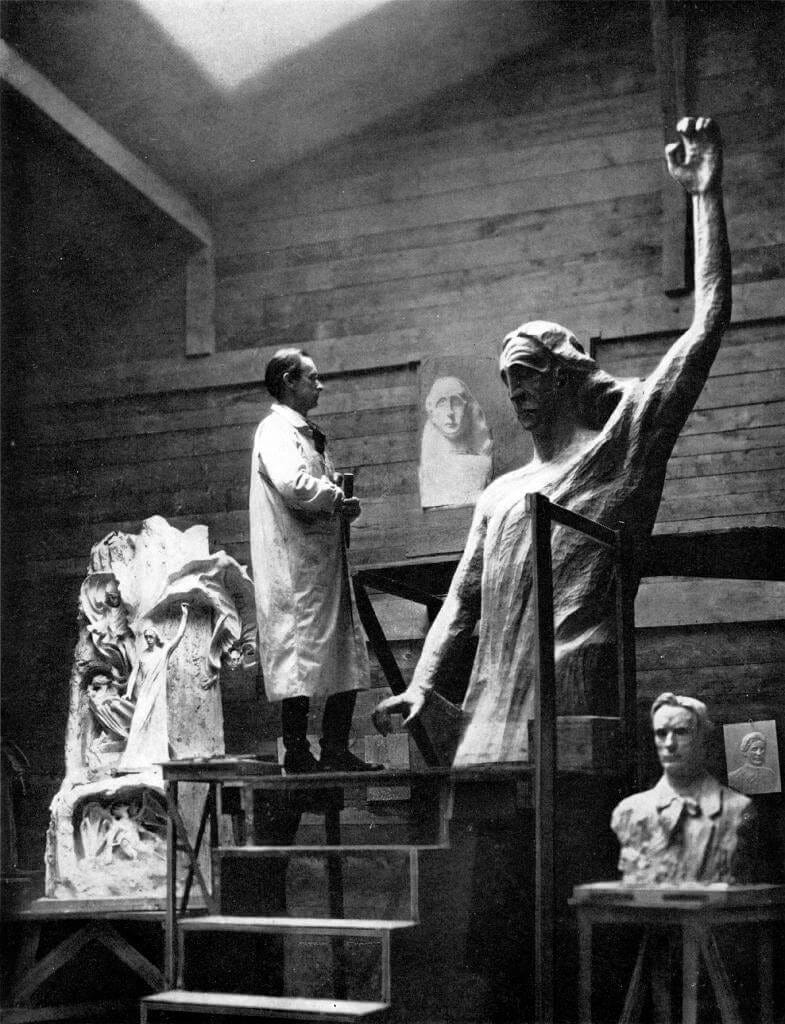

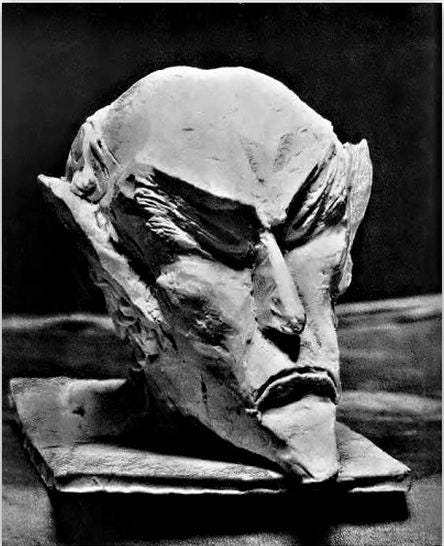

In the sculpture The Representative of Humanity (1917–1922), which Steiner created with Edith Maryon, Christ stands between Lucifer’s creative energy and Ahriman’s cold logic, calming and guiding both. The aim is not to pick sides but to maintain the threefold creative tension. To give it a slightly cringey business metaphor: Ahriman is the COO, Lucifer the CCO, and Christ the integrating CEO who grounds ideas without losing soul.

Ahriman in Action (Here and Now)

In modern life, Ahriman is taking over. We meet him daily, not as a cartoon villain, but as habits and systems that show up in familiar places:

AI and algorithms: Digital devices shape what we see, predict behaviours, and nudge desire. Deepfakes chip away at truth, automation replaces craft, and optimisation becomes the tech bro’s creed.

Social media: Platforms engineered for engagement harden thought into echo chambers, turning connection into comparison and fueling outrage and conformity.

Datafication: Modern societies increasingly value only what can be measured: grades, credit scores, fitness trackers, and endless statistics often define worth or success.

Pharmaceutical quick fixes: Chemical solutions promise swift relief yet often cause dependency or side‑effects, overtaking real wisdom and care.

Transhumanism and biotech: Neural implants, gene editing, and life‑extension treat bodies as upgradeable devices, neglecting the whole person.

Bureaucracy: Forms, metrics and KPIs transform relationships into dashboards, prioritising profit over people and process over presence.

Crypto and blockchain: Decentralisation promises freedom, but often fuels speculation over solidarity, echoing Steiner’s warning about technology outpacing moral progress.

Information overload: Technology’s flood of data overwhelms people with fragmented facts and constant news, encouraging surface-level thinking instead of deep understanding.

There’s no denying that Ahriman’s strengths help us build bridges and power grids. But when unbalanced, life can feel joyless and mechanical.

Bryan Johnson as a Mirror

A contemporary figure who invites Ahrimanic comparison is entrepreneur Bryan Johnson. His “Don’t Die” religion and “Blueprint” longevity programme is rooted in extreme quantification, monitoring hundreds of health metrics, adhering to AI-driven diets, taking handfuls of supplements, and experimenting with therapies like plasma transfusions.4 The goal is to achieve “age escape velocity,” meaning to biologically remain the same age or younger as time passes. But as Iain McGilchrist wrote recently:5

“The opposite of life is not death, but the machine. You are not a machine, and every person who suggests you are should be firmly, but politely, put right on the matter.”

Johnson’s hyper-disciplined approach treats the human body as a machine to be constantly optimised and life as a graph to be climbed, reflecting Ahriman’s tendency to reduce the organic and spiritual to data, calculation, and control. The result is a focus on technological mastery and measurable outcomes to dominate nature and conquer death, often at the cost of the more holistic or qualitative aspects of life.

Johnson’s regimen brings to mind philosopher Günther Anders and his idea of “Promethean shame.”6 Anders described the unsettling feeling when technology outperforms us, producing inferiority and surrendering our judgement and decision-making to machines. We end up adapting ourselves to suit technology, letting it shape our routines and self-image—a pattern easy to see in modern optimisation cultures.

In this sense, Johnson mirrors a broader cultural trend: outsourcing judgement, care, and even self-worth to advanced systems. Anders suggests this “shame,” a sense that humans don’t match up to their own creations, arises when trust is placed more in algorithms or metrics than our own instincts.

Johnson’s case raises useful questions we all face in an Ahrimanic world: how much do we let metrics or external systems decide what matters? Where do we trade nuance, intuition, or connection for control and certainty? And how do we balance being proactive about health with respect for the natural rhythms of life?7

These aren’t just theoretical questions, but profoundly personal and cultural dilemmas, magnified in an age where immortality seems to tempt ever closer through data and algorithms. To understand what might be lost in chasing such control, it’s worth recalling the American writer and environmentalist Edward Abbey, who resisted the cult of endless optimisation with blunt candor: “I do not believe in personal immortality; it seems so unnecessary. Show me one man who deserves to live forever.”8

In Abbey’s spirit, perhaps the challenge is not to calculate life’s extension, but to inhabit it more deeply, respecting the mystery and wildness that metrics can never measure.

A Quick Biochemical Aside: Serotonin and Rigidity

If you’re a regular reader, you’ll know I love nothing more than crowbarring in a connection to the biologist Ray Peat. Well here’s another intriguing echo: Peat challenged the popular image of serotonin as the “happy hormone,” describing it instead as a biochemical agent of stress, inflammation, and even depression.9 From a Peatian perspective, high serotonin parallels Ahriman’s rigidifying influence: it dampens energy production, fuels authoritarian traits, and contributes to aging and disease. Just as Ahriman grounds us in cold matter, serotonin enforces a biochemical conformity that stifles joy and creativity, turning life into hibernation and a grind of material survival.

Steiner’s Human Being

Steiner pictured the human being as layered: the physical body; a “life” (etheric) body which animates and energises the physical; an emotional (astral) body that contains feelings and desires; and a spiritual “I” or true self which provides individual consciousness and self-awareness. Lucifer pulls the astral upward into dreams; Ahriman drags the physical down into habits and numbness. The Christ impulse helps us integrate and choose wisely.

You can feel the tug-of-war between these forces play out in everyday choices. Why does scrolling social media (Ahriman) feel addictive yet empty? Why does daydreaming (Lucifer) inspire but distract? Why does a small act of care (Christ) restore proportion to a frantic day? As Steiner puts it:

“Human beings are dwellers in two worlds. Our uniqueness amongst the creatures of the earth lies in this role that we have as half beast and half angel. A dynamic tension exists because of the contrary demands which living in each of these realms places on us. We experience this on a daily basis, an internal tug-of-war, pulling first in one direction, then to the opposite pole. Whenever we are called upon to make a choice, a decision, the earthly and the heavenly draw us one way or the other and often both at once!”

Other Thinkers See Similar Patterns

Steiner’s triad echoes in many thinkers, evidencing a persistent pattern across traditions:

Martin Heidegger warned of modernity’s “enframing,” where everything becomes a calculable resource (a reductionist Ahrimanic mindset), and called for “poetic dwelling,” akin to the Christ impulse’s integration.

Iain McGilchrist describes the brain’s hemispheres: the left prioritising control and facts (Ahriman), the right meaning and metaphor (Lucifer), recommending balance as Christ does.

Carl Jung’s archetypes match: Lucifer as eternal youth, Ahriman as old ruler, Christ as Self integrating opposites.

Teilhard de Chardin’s “Omega Point” envisions matter-spirit convergence, echoing Christ’s synthesis.

William Blake portrayed Urizen (reason/Ahriman), Los (imagination/Lucifer), and the divine human (Christ).

Heraclitus saw opposites as integral parts of the same process, paralleling Steiner’s dynamic balance.

How We Might Practice Balance

Steiner said, “Lucifer and Ahriman must be regarded as two scales of a balance. It is we who must hold the beam in equipoise.” Practical steps we might take include:

Using technology humanely: favour tools that serve people, relationships, and communities rather than profit or control. This week, audit an app: does it foster connection or isolation?

Bringing creativity into everyday work: bring design, story, or play into “non‑art” roles like accountancy, engineering, and operations.

Grounding ideals in kindness: tie spirituality into small acts like listening, hospitality, honest craft, and care for bodies and communites.

Making room for tech-free spaces: device‑free mealtimes, unmeasured exercise, or analogue hobbies.

Strengthening discernment: practice saying “no” to habits that drain meaning, and “yes” to simple joys that enliven you.

Working with head, heart and hands each week: learn something, love someone, and make something, ensuring no single force monopolises your life.

The point isn’t to live in a neutral grey zone between extremes. Instead, it’s about moving with awareness: feeling the warmth of Lucifer’s fire without losing touch with reality, and standing firm in Ahriman’s steel without becoming cold and rigid. The Christ impulse is a wise love that holds both forces in balance and uses them for humanity’s good.

Embracing Steiner’s balance brings technology and dreams into harmony, turning crossroads into paths for growth.

You can get a fuller picture for Steiner’s work in this documentary, Science of Spiritual Realities:

Anthroposophy is a spiritual philosophy and research method founded by Rudolf Steiner in the early 20th century. It aims to explore the spiritual world and the nature of the human being through a path of knowledge that connects the spiritual dimension within us to the spiritual dimension of the universe. Anthroposophy integrates scientific thinking with spiritual insight and has practical applications in areas such as education, agriculture, medicine, and the arts. It emphasises human freedom and development, inviting individuals to explore inner and outer life with clarity and responsibility.

The Rudolph Steiner Archive: https://rsarchive.org/

Angra Mainyu is the destructive spirit in Zoroastrianism, representing chaos, evil, and opposition to the supreme god Ahura Mazda. According to Zoroastrian teachings, Angra Mainyu is the adversary of Spenta Mainyu, the “holy spirit,” and embodies all that opposes truth and order. This dualistic figure symbolises the eternal struggle between good and evil in ancient Persian religion and has influenced later cultural and spiritual ideas.

Steiner, R. (1919). Lucifer and Ahriman: Man’s responsibility for the Earth (GA 191) Lecture. Rudolf Steiner Archive. https://rsarchive.org/Lectures/19191101p02.html

“Blueprint” is a rigorous, science-based health and longevity program Johnson created to slow or reverse his body’s aging process. Blueprint serves as a practical foundation for Johnson’s broader “Don’t Die” religion, which extends beyond individual health to a philosophical and communal effort to overcome death and secure human survival amid the challenges posed by advancing AI technologies.

See: Bryan Johnson wants to start a new religion in which “the body is God” (MIT Technology Review article)

Can you still be human? Be aware of what is coming (Substack post)

Günther Anders and Promethean Shame: Our Unease in the Shadow of Our Creations (Substack post)

To be fair to Johnson, his transparency (especially on his failures), sense of humour, and his open‑science ethos complicate any simple verdict. It’s also worth remembering that Steiner’s idea of Ahriman describes a broad spiritual principle, not just an individual. The aim here isn’t to criticise one person, but to recognise patterns and reflexes in ourselves and our culture.

25 Ornery Aphorisms by Edward Abbey (Substack post)

Serotonin, depression, and aggression: The problem of brain energy (Article by Ray Peat)

Great post. I found it generated considerable self-inquiry. Currently pondering the optimising or maximising of biology/duration by Bryan and of external intelligence/compute by Sam whether we are missing an optimising of connection? We have plenty of chatter about serotonin and dopamine but where is the oxytocin revolution?

Wonderful synthesis John, thank you for sharing. I explored a similar sentiment (union of opposites) here: https://substack.com/@theotherinme/p-145193972

It's curious that the creative spark is referred to as Lucifer, given the negative connotations around that. Why do you think that is?