Amid the chaos of China’s Warring States period (475–221 BCE), a time of relentless conflict and clashing ideologies, a quiet yet profound text emerged: the Tao Te Ching, attributed to Lao Tzu, the “Old Master.”1 Likely compiled in the 4th or 3rd century BCE, this concise work blends poetic insight with philosophical depth, offering a radical alternative to the era’s rigid doctrines. While Lao Tzu’s existence as a Zhou dynasty archivist is uncertain, and he might even be a mythical or composite figure, the Tao Te Ching reflects a collective wisdom that challenged the thinking of its time.2

The Intellectual Crucible

The Warring States era, often called the Hundred Schools of Thought, was a hotbed of competing philosophies. Confucians like Mencius championed moral cultivation through ritual and education, Legalists like Han Fei advocated strict laws and centralised power, and Mohists preached universal love and meritocracy. Against these structured systems, philosophical Taoism (Daojia), distinct from the later more religious Taoism (Daojiao), stood apart. Embracing the Tao, the ineffable way of nature, Lao Tzu’s vision favoured concepts like wu wei (effortless action), emptiness, Te (inner virtue), and yielding to life’s natural rhythms over force or control. This countercultural philosophy invited alignment with the world’s spontaneous order, questioning whether top-down systems could ever foster true balance. For modern readers, the Tao Te Ching remains a timeless guide to authenticity in a culture that often prioritises coercion over flow.

The Tao: The Unnameable Current

The Tao, or “The Way,” is the subtle order of the universe, glimpsed in a river’s flow or the dance of a flock of starlings. The Tao Te Ching famously opens with a paradox: “The Tao that can be told is not the eternal Tao; the name that can be named is not the eternal name.” I realise the irony in exploring this in a written essay, yet the message is clear: defining the Tao limits it. It is a dynamic process, not a god or a law, seen in how things arise and fade. Chapter 42 states: “The Tao gives birth to the One; the One to the Two; the Two to the Three; and the Three to the ten thousand things.” This describes existence unfolding from wuji (the boundless void) through taiji (yin and yang’s interplay), embodying ziran—“naturalness” or things being authentically themselves.

Practically, following the Tao means observing before acting. A manager frustrated by a missed deadline might feel compelled to impose stricter rules, but Lao Tzu warns: “The more laws, the poorer people become.” By sensing her team’s needs and cultivating trust, she aligns with the Tao’s current. Similarly, when a colleague makes a subtle dig in a meeting, the Tao invites attunement: are they stressed, or is your pride hurt? Pausing to sense the situation’s pulse promotes harmony over conflict.

Wu Wei: Effortless Action

Wu wei, often mistranslated as “non-action,” means “effortless action” or “action in harmony with the Tao.” Chapter 48 notes: “In pursuing the Tao, every day something is dropped. Less and less is done, until non-action is achieved. When nothing is done, nothing is left undone.” This is not laziness or passivity, but action that moves seamlessly, like a gardener pruning just enough to nurture a plant’s healthy growth. Scholar Herrlee Creel called it “action without friction,” a kind of active ease.3 It’s often compared to Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s “flow” state, where we’re fully immersed in a task, but wu wei is less about personal performance and more about moving in tune with the world’s inherent cadence.4

Paradoxically, it requires discipline to sense when to act or hold back. Imagine working late to perfect a proposal. Wu wei might suggest intense focus, then rest, allowing ideas and energy (qi) to settle.5 This echoes the Taoist “80% rule,” a reminder never to push beyond four-fifths effort, preserving balance.6 In today’s hustle culture, wu wei challenges the urge to grind and force outcomes, inviting spontaneous alignment instead. Taoist practices like qigong, with their slow, fluid movements embody this wisdom. Overfill a cup and it spills; overwork, and you burn out. Wu wei offers a fundamental rethink, aligning effort with the world’s rhythm.

Emptiness: The Space of Possibility

Lao Tzu’s metaphor of emptiness highlights potential: “A cup is useful because it is empty.” Emptiness (xu) is not about nothingness but an opening, enabling pu, the “uncarved block” of pure simplicity and authenticity. Chapter 19 urges: “Manifest plainness, embrace simplicity.” Decluttering a workspace or simplifying a process reflects this. Livia Kohn describes emptiness as a “dynamic space of transformation,” alive with possibility.7 Taoist meditation fosters this openness, cultivating ziran and the zhenren—the “true person” who lives authentically and flexibly, free from rigid expectations. Chapter 15 praises such people for their “childlike heart,” full of wonder and receptivity.

This resonates across cultures. Song dynasty ink paintings use minimalist brushwork to leave space for imagination, akin to Japanese ma (the beauty of empty space). Modern research even links “time affluence” (having unstructured time) to well-being.8 An unfinished conversation can linger with meaning; an unscheduled afternoon can spark creativity. By slowing down, pausing the brushstroke or softening the breath, we open to life’s natural flow.

Te: The Power of Congruence

Te, often translated as “virtue” or “inner power,” is the Tao expressed through alignment. Chapter 54 states: “What is firmly rooted cannot be pulled out.” Unlike Confucian de, which emphasises moral cultivation through effort, Te arises naturally from attunement with the Tao. For example, consider a university lecturer swamped with marking at the end of a semester. In the rush, it’s easy to miss a student’s subtle struggle. But pausing to listen, to truly attune, is an expression of Te: an authentic influence without force. Similarly, modern leaders like Satya Nadella, who is said to foster empathy at Microsoft, reflect Chapter 17’s ideal of the “best leader whose presence is barely known.”9 Te isn’t about grand gestures but small, congruent actions that ripple outwards.

Western virtue ethics, such as Aristotle’s eudaimonia, call for deliberate practice of virtues like courage. In contrast, Te flows spontaneously from living in harmony with the Tao.10 As chapter 38 warns: “When the Tao is lost, there is Te; when Te is lost, there is benevolence.” In other words, contrived virtue is a pale substitute for authentic alignment.

Yielding: The Strength of Softness

Lao Tzu likens the Tao to water: “Nothing is softer than water, yet it overcomes the hardest stone.” Water yields, adapts, and persists, carving through rock over time. It fits any vessel, yet remains itself. Chapter 8 urges us to be like water: flexible, authentic, responsive. This reflects fan, the principle of return, where setbacks cycle back to new possibilities. Chapter 40 states: “Reversal is the movement of the Tao.” A career setback or a personal loss, approached with openness, may lead to unexpected paths and opportunities.

History offers examples of this principle in action. During the Three Kingdoms period, strategist Zhuge Liang famously outmanoeuvred stronger foes by adapting, waiting, and using his opponents’ force against them. Like water, his strength lay in flexibility, not raw power.11 In conversation, asking “What do you mean?” softens conflict and invites connection, an approach echoed in servant leadership. Confucians like Mencius criticised yielding as neglecting duty, but Lao Tzu sees wu wei as strategic timing, addressing issues with minimal friction, like water finding the path of least resistance. Yielding is not weakness but enduring strength.

The Dance of Yin and Yang

At Taoism’s heart is the interplay of yin (receptivity) and yang (assertion), complementary forces united, not opposed. As Chapter 42 notes: “The Tao gives birth to the One; the One to the Two,” with yin and yang generating the world’s multiplicity. Wu wei blends yin’s rest with yang’s action; Te emerges when yin’s softness aligns with yang’s strength. This dynamic balance mirrors the body’s homeostasis, where rest restores and action propels, each sustaining the other.

“China is the closest to our ideal of rich generality, especially its Taoist tradition with a dialectical awareness and emphasis on body, energy, and life.”12

These words from Ray Peat, the biologist-philosopher I’ve discussed before, capture the essence of a worldview that sees the body not as a machine, but as a dynamic field of intelligence, alive with energy and meaning.13 Peat’s modern lens on this ancient wisdom revealed metabolism, the body’s energetic fire, not merely as a biochemical process, but as a bridge to vitality and, strikingly, to luck. He believed that a robust metabolism, supported by simple practices like drinking coffee, amplifies synchronicities: those meaningful coincidences that feel like the universe is winking at us. This insight resonates with Chinese medicine, where metabolism fuels qi, the life force that nurtures the kidneys, which are seen as the source of yang’s spark and ming, our destiny or life mandate.14

Peat even saw tai chi, with it’s rich imagery, flowing movements, and slow, controlled breathing, as a way to support metabolism by increasing CO₂ levels in the body through gentle hypoventilation.15 A strong vital essence aligns us with life’s flow, inviting serendipity. Yet an ambitious professional, immersed in yang’s relentless drive, risks burnout. Restorative yin practices, like a quiet evening, a walk in nature, or Peat’s metabolism-supporting nutrition, helps restore equilibrium, enhancing health and attunement to life’s subtle cadence. As Peat might say, vibrant health aligns us with the Tao, and the world seems to conspire in our favour.

The ancient I Ching’s hexagrams model this balance, their shifting yin-yang patterns reflecting life’s flux.16 Chapter 24 of the Tao Te Ching cautions: “Those who stand on tiptoe don’t stand firm; those who rush ahead don’t go far.” Wisdom lies in honouring both forces.17 Vitality (e.g., mental clarity, effortless focus, fortunate encounters) signals consolidated essence, our ming shining brightly. Fatigue or rigidity, however, suggests a drift from the Tao. By nurturing our metabolic fire, as Peat suggests, we amplify yang’s spark within yin’s embrace, aligning with the Tao’s dynamic unity.

Taoism’s Living Legacy

Lao Tzu’s ideas live on in “longevity practices” such as qigong and tai chi, which embody wu wei and ziran through fluid movement. Zhuangzi, Lao Tzu’s philosophical heir, enriched this legacy with parables that challenge rigid thinking. In his butterfly dream, he dreams he is a butterfly, only to wake and wonder if he is a man dreaming of a butterfly or a butterfly dreaming of a man. This story questions fixed identities, inviting fluidity in how we see ourselves.18 Similarly, his tale of the “useless tree,” spared from being cut down for lacking conventional value, reflects pu, celebrating authenticity over societal expectations.19 These stories deepen Lao Tzu’s call to align with the Tao’s inherent rhythms.

Another Taoist parable, sometimes called “The Old Man Who Lost His Horse,” illustrates the belief that events are neither inherently good nor bad and should be met with calm acceptance, as their true meaning often revelas itself over time:

Philosophical Taoism resonates across diverse domains. Its influence on Zen Buddhism’s spontaneity and non-duality echoes in Thich Nhat Hanh’s teachings on mindful presence,20 while Jon Kabat-Zinn’s Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction channels wu wei, guiding people to meet stress with presence rather than resistance.21 Similarly, Pixar’s Soul (2020) reflects ziran, as its protagonist, Joey, learns to embrace life’s organic movement over rigid ambitions. From the global popularity of tai chi to research on post-traumatic growth, Lao Tzu’s call to embrace life’s cycles, drawing strength from flow, not force, continues to inspire.2223

Critics question whether ancient Taoist principles like wu wei can work in high-pressure arenas such as corporations or elite sport, where action often trumps restraint. Lao Tzu’s focus on timing and minimal friction reveals their potency: by aligning with the natural workings of the universe, wu wei fosters efficiency without force. As, Chapter 38 states: “The world is not won by forceful effort.” In corporate settings, leaders who build trust rather than micromanage achieve results with less strain,24 while research in sport psychology shows athletes embracing a “doing less” mindset often achieve better performance.25 Far from outdated, Taoism’s wisdom reveals routes to excellence in today’s fast-paced world.

The Path Forward

The Tao Te Ching is not a rulebook but a subtle guide, like moonlight illuminating a path. In a world of constant noise, instant opinions, and relentless productivity, Lao Tzu invites us to pause, listen, and move with life’s rhythm. Digital distractions, ceaseless productivity, and information overload can obscure the Tao’s gentle pulse, but small acts restore balance: silencing notifications, pausing for some qigong breathing (inhale for four, exhale for six), or resisting knee-jerk reactions realign us with life’s gentle flow.

Ask yourself: “What is unfolding?” Pause before acting. Simplify your schedule. Listen deeply in conversation. By embracing emptiness, cultivating Te, and yielding like water, we can navigate life with grace, finding resilience and peace in the Tao’s quiet current.

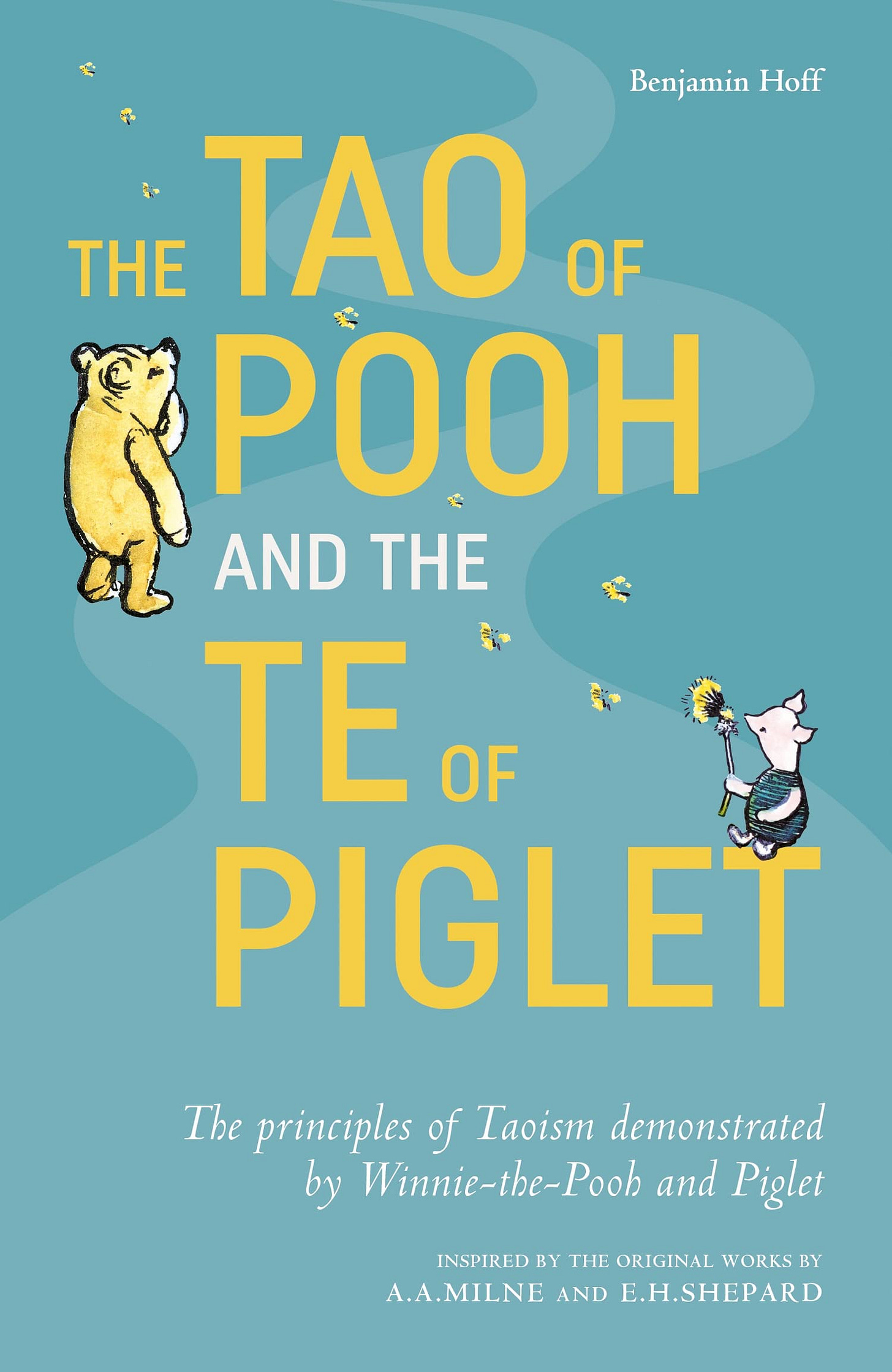

My favourite book on Taoism and a really good entry point for Western readers is The Tao of Pooh & The Te of Piglet by Benjamin Hoff. Originally two separate volumes, it uses the characters from A.A. Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh stories to introduce and explain key principles of Taoism. Pooh’s simple, effortless way of being aligns with living naturally, embracing simplicity, and going with the flow of life, while Piglet’s smallness and humility embody the “virtue of the small,” showing that true strength comes from modesty, kindness, and an open heart.

The name Lao Tzu is most accurately translated as “Old Master” or “Venerable Master.” The character 老 (lao) means “old” or “venerable,” and 子 (zi) is an honorific meaning “master” or “philosopher,” commonly used for respected teachers in ancient China.

Sima Qian’s Records of the Grand Historian is a monumental historical text completed around 94 BC during the Western Han dynasty. It is considered the first comprehensive history of China and covers approximately 2,500 years, from the legendary Yellow Emperor to the reign of Emperor Wu of Han.

Creel, H. (1970). What Is Taoism? University of Chicago Press.

Csikszentmihalyi’s “flow” state is a mental state in which a person becomes fully immersed, energised, and focused on an activity, to the point that everything else fades away. Self-consciousness disappears, distractions are excluded, and time seems to pass differently. Flow occurs when there is a balance between the challenge of the task and the individual’s skill level, and when the activity has clear goals and immediate feedback. People in flow are so engaged that the activity feels intrinsically rewarding, and they often describe it as their “optimal experience” or being “in the zone.”

Qi (sometimes spelled chi) is often translated as “vital energy,” “breath,” or “life force.” It is the dynamic, flowing energy that animates all living things and permeates the universe. In the Tao Te Ching, qi is not explicitly named but is implied in the Tao’s generative process. In broader Taoist practices, qi is central to concepts of health, movement, and harmony, as seen in qigong and tai chi, where it is cultivated through breath, motion, and meditation.

Qigong (pronounced “chee-gong”) is an ancient Chinese practice that combines coordinated movements, controlled breathing, and meditation to cultivate and balance qi-the body’s vital life energy. The word “qigong” comes from “qi” (life force or energy) and “gong” (work or cultivation), so it literally means “energy work” or “cultivating energy.”

Kohn, L. (2001). Daoism and Chinese Culture. Three Pines Press.

Kasser, T., & Sheldon, K.M. (2009). Time Affluence as a Path toward Personal Happiness and Ethical Business Practice: Empirical Evidence from Four Studies. Journal of Business Ethics, 84 (Suppl 2), 243–255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-9696-1

Kasser & Sheldon found that time affluence—the sense of having enough free time—was a significant and consistent predictor of happiness and subjective well-being, even after controlling for material wealth. Across four studies, they showed that people who felt more time affluent reported higher satisfaction with life, greater feelings of autonomy and competence, more positive relationships, and were more likely to engage in personally meaningful activities. Their research suggests that having ample time is more closely linked to happiness than simply having more money, and that prioritising time affluence can lead to greater well-being.

How Empathy Helped Generate A $2 Trillion Company (Forbes article)

Aristotle’s (384-322 BCE) eudaimonia is the concept of the highest human good, often translated as “flourishing” or “living well,” rather than simply “happiness” in the modern sense. For Aristotle, eudaimonia is not a fleeting feeling or pleasure, but an enduring state achieved by living in accordance with reason and cultivating virtues (excellences of character and intellect) over a complete life. He argued that every being has a unique function, and for humans, this is rational activity. Therefore, eudaimonia consists in performing rational activities excellently; that is, living virtuously. This requires not only moral and intellectual virtues developed through habituation and reflection, but also some external goods, such as friendship, health, and a degree of material well-being. Eudaimonia is thus an active, lifelong process of fulfilling one’s potential as a rational and social being.

Zhuge Liang (181–234 CE) was a renowned strategist, statesman, and chancellor of the state of Shu during the Three Kingdoms period of China (220–280 CE). He is celebrated for his exceptional intelligence, adaptability, and use of psychological strategy: qualities that align closely with the Taoist ideal of strength through flexibility. One of the most famous stories (from the Romance of the Three Kingdoms, a historical novel based on real events) describes Zhuge Liang outwitting a much larger enemy force by calmly sitting atop an open city gate, playing his zither. The enemy, suspecting an ambush, retreated without attacking. This episode exemplifies using psychological insight and minimal action to achieve victory. Historically, Zhuge Liang was known for his patience, careful timing, and ability to adapt his strategies to changing circumstances, often avoiding direct confrontation and instead using the terrain, weather, and his opponents’ expectations against them.

Education, Energy, and Ideology (article by Ray Peat).

Ray Peat and the Art of Becoming: A Philosophy of Aliveness (Substack post)

In Chinese medicine, ming is most accurately translated as destiny or life mandate. It is closely tied to one’s original nature (xing) and is seen as the pattern or blueprint for a person’s life, influencing both their physical constitution and their fate. In classical Chinese medicine and philosophy, health involves understanding and living in harmony with one’s ming, fulfilling the natural order inscribed within, rather than resisting or attempting to force a different path. While ming can sometimes be colloquially associated with “luck,” in Chinese medicine it has a much deeper meaning, emphasising destiny, purpose, and the unfolding of one’s potential rather than random good or bad fortune.

Protective CO2 and aging (article by Ray Peat)

The I Ching (also known as the Yijing or Book of Changes) is one of the oldest and most influential Chinese classic texts, originating in the late 9th century BC during the Zhou dynasty. It began as a divination manual and evolved into a foundational work of Chinese philosophy and cosmology. At its core, the I Ching consists of 64 hexagrams-symbols made up of six stacked lines, either broken (yin) or unbroken (yang). Each hexagram represents a specific situation or principle of change and is accompanied by interpretive texts that offer guidance or wisdom. Traditionally, users consult the I Ching by casting coins or manipulating yarrow stalks to generate a hexagram, which is then interpreted to provide insight into a question or decision.

Rather than being absolute opposites, yin and yang are two aspects of a dynamic, ever-changing balance that underlies all phenomena. The classic symbol of yin and yang—a circle divided into black (yin) and white (yang) halves, each containing a dot of the other—illustrates that each force contains the seed of its opposite, and that neither is superior. The interaction and balance between yin and yang are believed to generate the cycles and changes observed in nature, such as day and night, the seasons, and even human behaviour and health.

Zhuangzi’s parable of the butterfly is one of the most famous stories in Taoist philosophy. In it, Zhuangzi describes how he once dreamed he was a butterfly, happily fluttering about, completely unaware that he was Zhuangzi. When he awoke, he found himself to be unmistakably Zhuangzi again. But then he wondered: was he Zhuangzi who had dreamed he was a butterfly, or a butterfly now dreaming he was Zhuangzi? He concludes that there must be a distinction between the two, yet this uncertainty is called the “transformation of things.” For Zhuangzi, this story illustrates the Taoist view that all things are in constant transformation, and what we take as fixed reality may itself be just another phase or perspective within the ongoing flow of existence.

Zhuangzi’s parable of the useless tree tells of a massive, old tree with twisted, knotted branches and wood unsuitable for carpentry, so no one cuts it down or uses it for anything practical. When a carpenter and his apprentice encounter the tree, the apprentice marvels at its size and beauty, but the master explains that its “uselessness” is exactly why it has survived so long: because it cannot be made into tools, boats, or furniture, no one harms it, and it thrives in peace.

Thich Nhat Hanh’s “mindful presence” is the practice of bringing your full awareness to the present moment, with openness, gentleness, and compassion. It means uniting mind and body in whatever you are doing—breathing, walking, eating, listening—so you are truly there, attentive to yourself, others, and the world around you.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain, and Illness. New York: Delacorte.

Quan, L., Lü, Q., Sun, B., Zhao, X., & Sang, J. (2022). The relationship between childhood trauma and post-traumatic growth among college students: The role of acceptance and positive reappraisal. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, Article 921362. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.921362

Kelly J. D., 4th (2022). Your Best Life: In the Lowest Moments, An Opportunity for Post-traumatic Growth. Clinical orthopaedics and related research, 480(1), 33–35. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8673980/

Micromanaging Leaders Are Setting Their Teams Up For Failure (Forbes article)

Kee, Y. H., Li, C., Zhang, C.-Q., & Wang, J. C. K. (2021). The wu-wei alternative: Effortless action and non-striving in the context of mindfulness practice and performance in sport. Asian Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1(2-3), 122–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajsep.2021.11.001

I'm a Chinese.

“The Tao that can be told is not the eternal Tao; the name that can be named is not the eternal name.”

Name 名,is a unique terminology in Buddhism, but it does not mean 'name'.

名 is defined as "Mind, Consciousness" in Buddhism.