Clare Graves and the Evolution of Human Consciousness

A Quest for Understanding Human Potential

What does it mean to thrive as a human in a rapidly changing world?

Clare Graves (1914-1986) never claimed to have the final answer, but he offered a remarkably useful map. A psychologist by training, Graves wasn’t interested in diagnosing dysfunction or pathology. Instead, he sought to understand how people grow, adapt, and unfold their potential in response to life’s challenges. His guiding question was simple yet profound:

How do human beings evolve psychologically over time, both individually and collectively, as life conditions change?

This question launched a decades-long investigation beginning in the 1950s at Union College, New York. Graves conducted extensive surveys and interviews with students and professionals, collecting thousands of responses about their values and worldviews. While his methods lacked today’s quantitative rigour, they revealed fascinating patterns in how people’s thinking evolves as life conditions change. The result was his “Emergent Cyclical Levels of Existence Theory,” a dynamic framework that illuminates the interplay between external realities and internal capacities, offering a lens for understanding human consciousness across contexts.

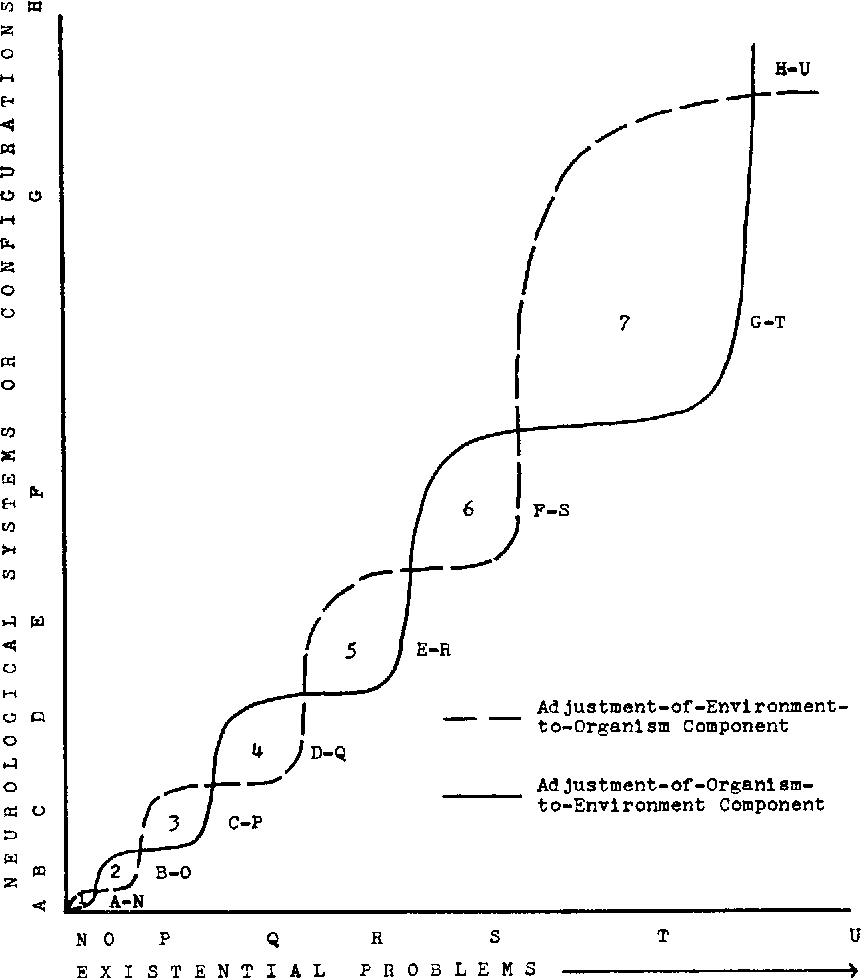

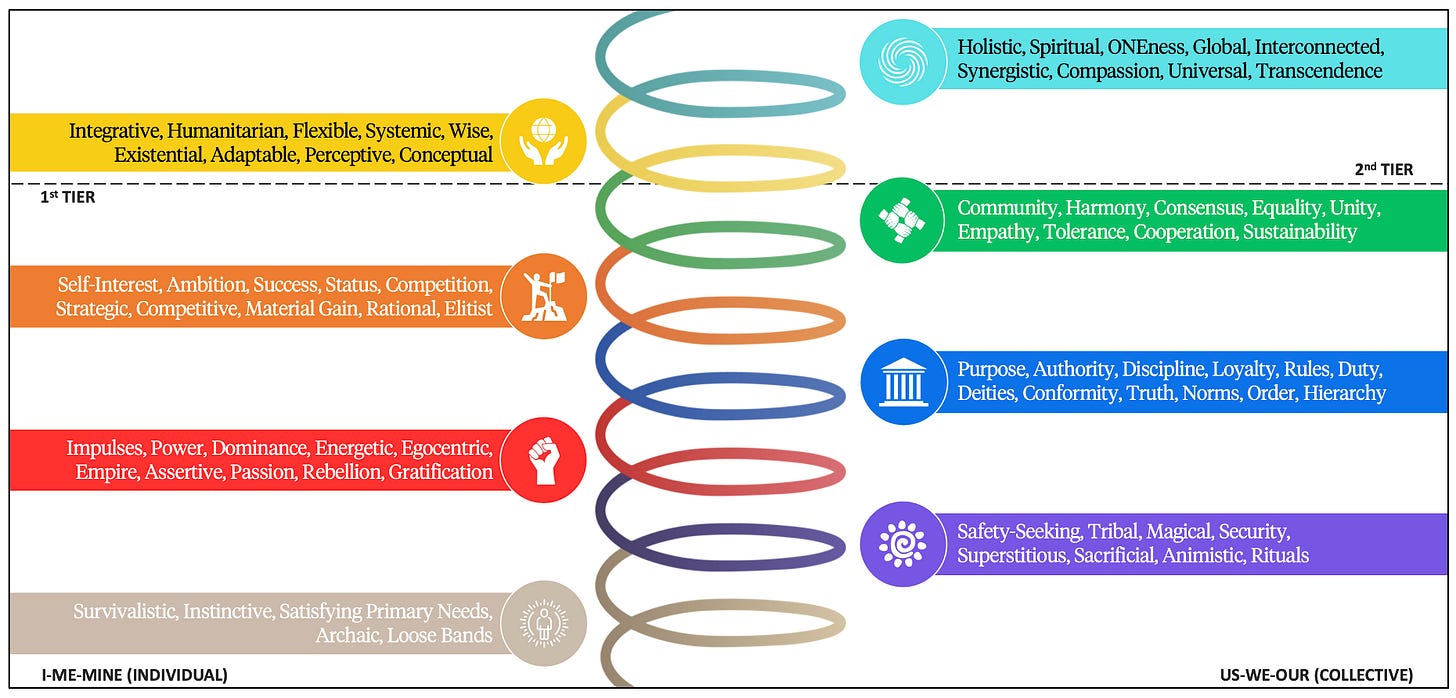

The Double-Helix Model

At its core, Graves’ theory is built on a double-helix: the intertwining of “life conditions” (social, economic, environmental, or cultural challenges) with “coping systems” (psychological and behavioural capacities for adaptation). As he put it: “Man does not live at one level of existence but oscillates between them, depending on the problems he faces and his ability to cope.” Human development, in this view, is not a linear climb toward an ideal state but a spiralling journey, always adjusting to new and more complex challenges.

Unlike Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, which sees “self-actualisation” as the end goal, Graves believed that psychological growth is infinite, with no ultimate stage of being fully developed. “Human psychological development is an open-ended process,” he wrote, “for as long as new problems arise, man will generate new solutions.”1 He suggested that adaptive leaps might match changes in our neurobiological capacities, from simple survival instincts to more complex integrative thinking. However, this was more of a concept than something proven by clinical evidence. A defining feature of his model is the oscillation between self-expressive (individualistic) and self-sacrificial (collectivist) modes at each level, reflecting humanity’s perennial tension between autonomy and belonging.

When existing worldviews fail to address new challenges, individuals or groups face a threshold: they may regress to simpler patterns, stagnate in disequilibrium, or leap to a more complex coping system if equipped with the capacity and support. This framework laid the foundation for Spiral Dynamics, later developed by Don Beck and Chris Cowan, who introduced a structured colour-coding system and applied it to organisational contexts.2 It also influenced Ken Wilber’s Integral Theory,3 though Graves’ focus remained distinctly empirical, rooted in observable human values and real-world contexts.

“The psychology of the mature human being is an unfolding, emergent, oscillating spiraling process marked by progressive subordination of older, lower-order behavior systems to newer, higher-order systems as man’s existential problems change.” —Clare Graves

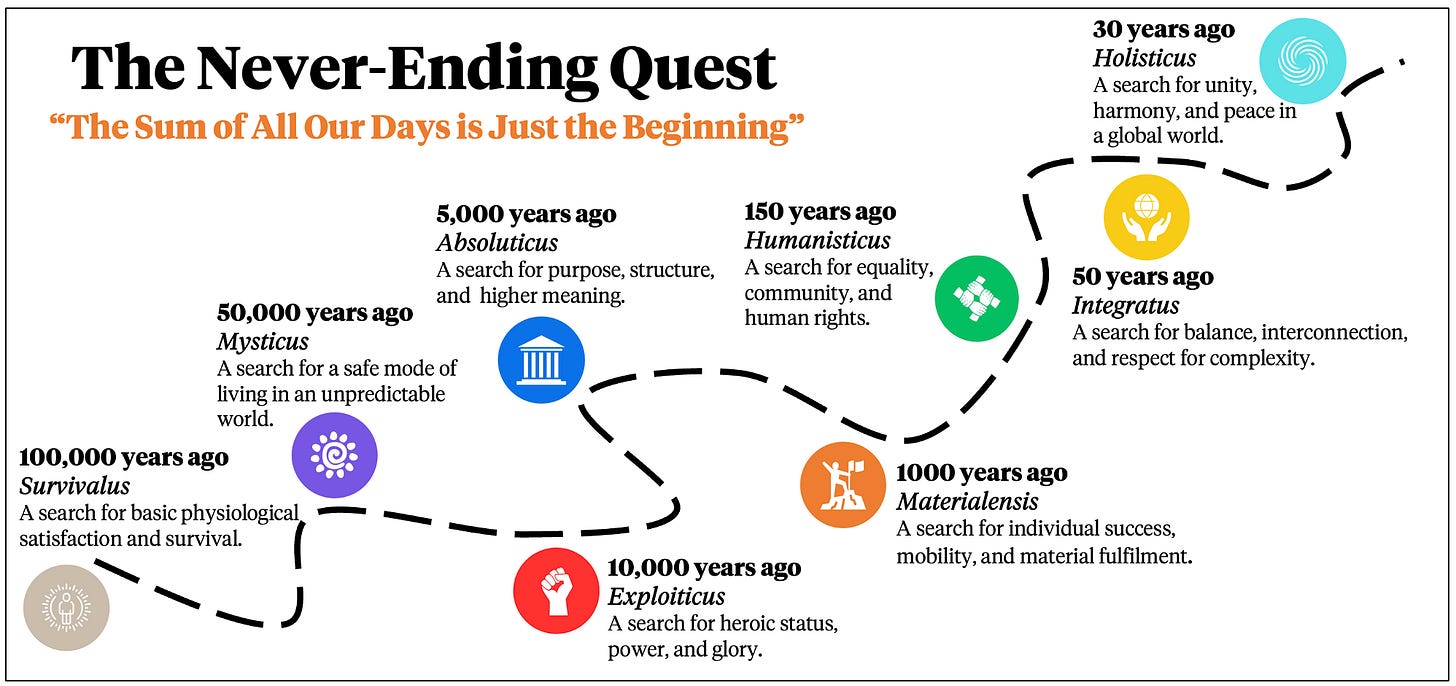

The Emergent Stages of Existence

Graves identified a sequence of developmental stages, each representing a qualitatively different worldview and coping system tailored to specific existential conditions. No stage is morally superior; each is functional in its context but becomes limiting when stretched beyond its adaptive capacity. Higher stages, however, offer greater complexity and integrative potential for addressing broader challenges. Importantly, these stages are not rigid categories but nested systems, building upon and incorporating earlier capacities. Graves originally labelled these levels with letter pairs (e.g., A-N, B-O). To make things easier, I’ve combined them with the Spiral Dynamics colour-coding below. As you read through, consider which stage most feels like you.

First Tier Stages

1. Beige (A-N): Survivalistic

Driven by raw, instinctive responses to immediate physiological needs: food, water, shelter. This stage characterises newborns, individuals in extreme deprivation, or survival scenarios. Thinking is reactive, with no foresight or social awareness.

Metaphor: Life is Survival. Way: The Primal Way. Challenge: Inability to plan or connect socially limits adaptation beyond immediate survival.

2. Purple (B-O): Tribalistic

Centred on safety and belonging through group cohesion, magical beliefs, and ancestral rituals, this stage is prevalent in traditional societies, clans, or tight-knit communities. Loyalty to the tribe and reverence for tradition dominate.

Metaphor: Life is a Ritual. Way: The Traditional Way. Challenge: Superstition and resistance to change hinder innovation or external integration.

3. Red (C-P): Egocentric Power

Marked by assertive, impulsive drives for dominance, glory, and immediate gratification, this stage fuels warlord cultures, gangs, or heroic mythologies. The self is paramount, with little regard for others’ needs.

Metaphor: Life is a Battle. Way: The Powerful Way. Challenge: Lack of empathy risks violence, exploitation, or social fragmentation.

4. Blue (D-Q): Absolutistic Order

Guided by structure, rules, and a higher authority (e.g., religion, law, or government), this stage values purpose through discipline and moral codes. Found in religious orthodoxy, bureaucracies, or stable societies, it provides order but resists deviation.

Metaphor: Life is a Test. Way: The Righteous Way. Challenge: Rigidity and dogmatism suppress creativity or dissent, stifling adaptability.

5. Orange (E-R): Strategic Achievement

Prioritising autonomy, reason, and measurable success, this stage drives capitalism, scientific progress, and individual ambition. Seen in tech startups, entrepreneurial ventures, or competitive fields, it champions innovation and opportunity.

Metaphor: Life is a Game. Way: The Winning Way. Challenge: Materialism and focus on individual gain create social and environmental blind spots.

6. Green (F-S): Humanistic Community

Focused on equality, empathy, inclusivity, and ecological awareness, this stage emerges as a reaction to Orange’s excesses. Evident in social justice movements, cooperative communities, or environmental activism, it seeks consensus and connection.

Metaphor: Life is a Cause. Way: The Shared Way. Challenge: Reluctance to prioritise or make tough decisions leads to paralysis or inefficiency.

Second Tier Stages

7. Yellow (G-T): Integrative Systems Thinking

Flexible and contextual, this stage thrives on paradox and systemic problem-solving, valuing all prior stages’ contributions. It adapts strategies to specific challenges, seen in interdisciplinary thinkers or adaptive leaders.

Metaphor: Life is a System. Way: The Adaptive Way. Challenge: Its complexity can appear aloof or elitist, making it hard to translate into broad movements.

8. Turquoise (H-U): Holistic Global Awareness

Viewing humanity as part of a larger living system, this stage emphasises global consciousness, ecological integration, and spiritual wholeness. It seeks to align human systems with planetary well-being, though it remains rare and emergent.

Metaphor: Life is a Flow. Way: The Universal Way Challenge: Its abstract nature makes practical implementation difficult.

Graves described the shift from First Tier to Second Tier as a “momentous leap” toward intrinsic complexity, where individuals and systems integrate all prior stages rather than being driven by deficits. These stages, only beginning to emerge in Graves’ time, are increasingly critical for addressing today’s interconnected challenges.4

Consciousness in Organisations and Cultures

Graves’ model applies not only to individuals but also to organisations, cultures, and civilisations, reframing conflicts as mismatches between coping systems. A Blue-minded organisation, rooted in hierarchy and tradition, may struggle to collaborate with an Orange startup chasing disruption and profit. Neither is inherently superior; each is attuned to different existential problems. Recognising these dynamics allows leaders to bridge divides and foster synergy.

For example, the gig economy reflects Orange’s pursuit of autonomy and flexibility, disrupting Blue’s preference for stable, hierarchical employment. Workers are caught between the freedom of gig work and the security of traditional jobs. Meanwhile, Green-led climate activism, with its emphasis on inclusivity and ecological care, often clashes with Orange’s technological optimism or Blue’s regulatory frameworks. A Yellow-minded leader could integrate these by designing policies that balance economic innovation, job stability, and environmental sustainability, turning tension into collaboration.

Historical and Contemporary Dynamics

History illustrates these developmental waves. Medieval Europe, dominated by Blue’s hierarchical order, gave way to the Enlightenment’s Orange rationalism and progress. Today’s social movements embody Green’s focus on equality and pluralism. Yet, in modern society, all stages coexist and often collide: Red’s raw power in geopolitics, Blue’s structure in legal systems, Orange’s ambition in technology, and Green’s empathy in social justice initiatives.

Big challenges today like climate change, AI ethics, and global migration are simply too complex to be solved by any single stage. Rapid technological shifts disrupt Blue’s stable structures, while cultural polarisation pits Green’s inclusivity against Purple’s tribalism or Red’s dominance. Graves’ model suggests that Second Tier thinking, particularly Yellow’s integrative systems approach, is essential for navigating this complexity. For instance, governing AI development requires blending Blue’s ethical principles, Orange’s innovation, and Green’s concern for societal impact. A Yellow framework might create adaptive regulations that evolve with technology, while Turquoise could inspire a global ethos of shared responsibility.

Graves’ spiral equips us to navigate complexity with more flexibility, seeing each stage as a useful tool in a developmental toolkit. The real challenge is not that these stages exist, but our tendency to cling to them too tightly, turning adaptive solutions into dogmas.

Navigating Transitions and Regression

Development is sequential and inclusive: each stage builds upon and integrates earlier capacities. To embody Green’s compassion, one must first develop Red’s assertiveness, Blue’s discipline, and Orange’s autonomy. Skipping stages creates psychological fragility, because when we miss out on important growth steps, it weakens our overall stability.

Transitions happen when life throws up challenges that the current way of seeing the world can’t handle, pushing individuals or groups into a state of imbalance. At this threshold, they may regress to earlier patterns (e.g., a Green idealist reverting to Blue’s moral certainties under stress), stagnate in confusion, or leap to a more complex coping system if supported by capacity and resources. Graves emphasised that mature individuals can operate across multiple levels, selecting the mindset most appropriate to the situation: “The mature human being is one who can move fluidly between levels of existence, choosing the one best suited to the context.”

Each individual or group anchors in a “centre of gravity,” the developmental stage where they usually operate, shaped by their skills, background, and environment. But our immediate context can quickly shift us. For example, a car accident may drive a Green empath to Beige’s survival instincts, a sudden promotion could spark Orange ambition in a Blue traditionalist, or a profound loss might evoke Turquoise’s holistic reflections in a Yellow thinker. This fluidity reveals a common misstep: many claim Yellow’s integrative thinking, confusing intellectual curiosity or idealism with the consistent, context-adaptive maturity Yellow requires. Graves warned about “Level 5” (Orange) wanting to be acknowledged as “Level 7” (Yellow). Similarly, Chris Cowan warned that what people often claim to be Turquoise thinking is simply Orange trying to pass itself off as Turquoise.

True stage embodiment requires navigating life’s unpredictable challenges, refining one’s center of gravity while expanding the capacity to respond appropriately across contexts. Regression often surfaces under contextual pressure, but glimpses of higher-stage thinking are possible, even if not yet stable. This fluidity underscores the dynamic nature of Graves’ model, where growth is not about reaching a final state but about adapting continually.

A Framework for Understanding Consciousness

Graves’ model resonates with other developmental theories. Like Maslow’s hierarchy, it sees basic needs (Beige’s survival, Purple’s safety) as prerequisites for higher concerns (Green’s belonging, Yellow’s integration).5 Like Lawrence Kohlberg’s moral stages, it traces a progression from Red’s egocentrism to Blue’s rule-based ethics to Green’s universal care.6 Jane Loevinger’s ego development echoes Graves’ shift from impulsive (Red) to conformist (Blue) to integrated (Yellow) selves.7 While Graves’ framework lacks modern empirical validation and may oversimplify cultural nuances, its emphasis on adaptive consciousness remains a powerful tool for navigating complexity.

In a world that’s changing fast, Graves offers us a living map of human potential, enabling us to understand how individuals, organisations, and even whole societies grow and change. His ideas encourage us to look beyond fixed labels, face challenges with new skills, and welcome the future with curiosity and strength.

Becoming Fully Human

Graves described his work as “a psychology of the mature human being.” Not perfect or complete, but dynamic, complex, and ever-learning. To live syntropically, fostering growth and harmony as life unfolds, means understanding and moving through different stages of consciousness.8 It means recognising that what looks like resistance or regression in others might actually be the stage they need to be in right now. It means noticing your own layers: a longing for Blue’s stability, a spark of Red’s power, a pull toward Green’s connection, or an aspiration for Yellow’s integration, and wielding them wisely.

In conflicts—whether a workplace disagreement or a global crisis—pause to consider: How is this perspective shaped by its developmental stage, and how can I integrate it with others? Reflect on your own worldview: Are you anchored in Blue’s order, chasing Orange’s success, yearning for Green’s community, or glimpsing Yellow’s systems thinking? Growth is not about choosing one “right” way to live but about becoming more fully human, stage by stage.

Graves’ spiral reminds us that “the present is but a moment in the process of becoming.” As you navigate your life and the world around you, observe the stages at play. Where will your next leap take you, and how will it shape the unfolding of human consciousness?

The below video is one one of the very few interviews of Clare Graves conducted by Don Beck and Chris Cowan. In it, Graves gives an overview of his lifelong work on the Levels of Existence model, more commonly known now as Spiral Dynamics.

The book, The Never Ending Quest: Dr. Clare W. Graves Explores Human Nature was published posthumously in 2005, nearly three decades after Graves began drafting it and nearly twenty years after his death. It was compiled and edited by Christopher Cowan and Natasha Todorovic, who drew from Graves’s unfinished manuscript, published and unpublished writings, recorded presentations, and seminars. It is considered the definitive source on Graves’s work.

Clare Graves and Abraham Maslow were contemporaries in psychology and had a collegial relationship. Graves began his research specifically trying to rationalise and validate Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, and the two were in contact, discussing their respective models. However, Graves ultimately found Maslow’s approach limited and could not fit his own research data within Maslow’s conceptual scheme. Graves concluded that while Maslow’s idea of self-actualisation was important, it was only one possible way of being, not an end state for all humans. Graves’s model proposed that human development is cyclical and open-ended, rather than a fixed hierarchy culminating in self-actualisation as Maslow suggested. Later in life, Maslow recognised the limitations of his own hierarchy and was open to Graves’s ideas. Some accounts suggest that Maslow understood and accepted Graves’s model in their discussions and even began to doubt whether self-actualisation was truly a final end state.

Their relationship began when Beck, a professor at the University of North Texas, became interested in Graves’ work and worked closely with him; Beck then introduced his graduate student, Chris Cowan, into the collaboration. Together, Beck and Cowan sought to make Graves’ complex, research-based theory more accessible and practical. They applied the model in real-world contexts, including organisational consulting and large-scale social change projects, most notably in South Africa during the transition from apartheid. Their collaboration resulted in the influential 1996 book Spiral Dynamics: Mastering Values, Leadership, and Change, which remains the foundational text for the model.

Over time, differences emerged between Beck and Cowan, especially regarding the commercialisation and direction of Spiral Dynamics. They ended their collaboration in 1999 after an acrimonious split. One of the main reasons for their falling out was Cowan’s opposition to Ken Wilber’s interpretation and integration of Spiral Dynamics, which Cowan regarded as overly spiritual and not aligned with Clare Graves’s original theory. After the split, Beck began collaborating with Ken Wilber, launching the Spiral Dynamics Integral (SDi) brand and aligning Spiral Dynamics with Wilber’s integral theory. Cowan, on the other hand, distanced himself from both Beck and Wilber, maintaining a more orthodox interpretation of Graves’s work and criticising Wilber’s and Beck’s adaptations.

Graves’ article Human Nature Prepares for a Momentous Leap (PDF), published in The Futurist in 1974, is a foundational presentation of his theory of human development. The article emphasises that most of human history has been spent in the “first tier” levels, and he identifies a coming “momentous leap” to a “second tier” of existence, which he suggests will be fundamentally different. Graves proposes that humanity faces a choice among three possible futures:

Regression to earlier, more primitive stages if existential threats are not managed.

A dystopian, authoritarian future.

The emergence of the second tier, enabling humanity to address global challenges with new capacities for integration and complexity.

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (1943) is a psychological theory that organises human motivation into a five-tier model, often visualised as a pyramid. Maslow originally proposed that lower needs must be satisfied before higher needs become motivational, though later research and expansions of the model suggest that people may pursue multiple needs simultaneously and that the hierarchy is not strictly linear. In later years, Maslow expanded the model to include additional stages such as cognitive needs (knowledge, understanding), aesthetic needs (appreciation of beauty), and transcendence (helping others achieve self-actualisation), but the five-stage model remains the most widely known.

Lawrence Kohlberg’s moral development model (1958) is a theory describing how people progress in their moral reasoning through three main levels, each containing two stages, making a total of six stages. The model emphasises how individuals justify their moral decisions, not just the decisions themselves. Kohlberg’s framework is widely used in psychology and education to understand how moral reasoning develops and why people make the moral choices they do.

Jane Loevinger’s ego development model (1976) is a comprehensive theory describing how the ego—the frame of reference individuals use to interpret themselves and the world—matures through a series of sequential, hierarchical stages across the lifespan. Rooted in the work of Erik Erikson and Harry Stack Sullivan, Loevinger’s model views the ego as a dynamic process shaped by the interaction between the inner self and the external environment.

Syntropy and the Cosmic Seesaw (Substack Post)