Ray Peat (1936-2022) was an American biologist, painter, teacher, and philosopher, who spent his life challenging what we’ve been taught about life: its mechanics, its purpose, its so-called inevitable decline. He saw it differently. Not as a machine grinding down under entropy, but as a creative process, always unfolding, alive with intelligence and energy. His ideas question the foundations of modern science, painting a picture where matter pulses with memory, energy weaves meaning, and time builds complexity instead of tearing it apart. This isn’t a tale of decay, it is one of becoming. A call to see ourselves as living histories of energy flow, shaping the world with every breath, thought, and choice.

“What could be more important to understand than biological energy? Thought, growth, movement, every philosophical and practical issue involves the nature of biological energy.” — Dr Ray Peat

Against Mechanism: The Trap of Reductionism

Ever since humans invented language, we’ve sliced reality into neat abstractions: matter as inert, energy as its spark, life as a mechanism. These categories helped us make sense of the world, but over time, they became idols. We began to mistake our maps for the territory. Biology, Peat argued, fell into this trap, adopting physics’ obsession with universal laws and reducing life to deterministic parts: genes as blueprints, receptors as locks and keys, behaviour as the output of blind forces. Peat called this a religious belief about matter, not science. It wasn’t just wrong, it was spiritually deadening.

The problem with reductionism is that it misses emergence. Living systems do things their parts can’t do alone: adapt, feel, create, understand. A single neuron doesn’t think, but a brain does. A gene doesn’t evolve, but an organism does. Life cannot be explained by chopping it up and studying the pieces. It is not a sum of parts, but a living, unfolding process.

Take the immune system: a dynamic web of cells, signals, and memories that adapts to threats in real-time, often in ways that defy simple genetic scripts. Or the nervous system: billions of neurons firing in synchrony to generate thought, emotion, and awareness—phenomena that vanish when reduced to a single synapse. These are not machines, they are symphonies, each note meaningless without the whole. Peat’s critique isn’t just some abstract theory; it’s a call to rethink how we approach health, science, and life itself. To shift from dissecting life to understanding it as a dynamic, integrated whole. If we only see parts, we miss the music.

Iain McGilchrist and the Dance of Attention

This vision finds a surprising ally in the British psychiatrist and philosopher, Iain McGilchrist,1 whose work on the brain’s hemispheric differences dovetails beautifully with Peat’s ideas. McGilchrist shows that how we pay attention shapes what the world becomes for us. The left hemisphere loves to abstract, classify, control: it’s all about maps over terrain, formulas over forms. The right hemisphere, on the other hand, sees wholes, thrives in context, and connects through lived, embodied meaning. McGilchrist warns that when the left hemisphere dominates, life gets reduced to a mechanism, and depth collapses into control.

Peat’s critique of modern biology reads like a physiological version of McGilchrist’s cultural warning. Both see a society drifting away from participation toward prediction, from life as experienced to life as explained. For Peat, this drift comes from a metabolic imbalance, a society low on energy, high on rigidity, clinging to narrow certainties. McGilchrist’s hemispheres give us a neural picture of this: the left’s tight focus mirrors a stressed, energy-starved state, while the right’s openness requires the metabolic abundance Peat championed. To reclaim vitality, both say, we need to restore balance, not just in our brains, but in how we engage with the world. That means leaning into the right hemisphere’s way of knowing: holistic, relational, open to possibility.

Teleology: The Intelligence of Becoming

For Peat, life wasn’t just something that happens, it was something that aims. This is where his philosophy gets quietly revolutionary: he brings purpose back into a universe that science has stripped of it. Much like Aristotle’s “formal cause,”2 Peat’s teleology is emergent, adaptive, contextual, creative, a drive toward greater coherence, complexity, and vitality. He found a kindred spirit in Alfred North Whitehead’s process metaphysics, where the universe is not composed of static things but of events: “actual occasions” of becoming.3 Life, in this view, isn’t just pushed by past causes; it is pulled toward possible futures. It is anticipatory, inventive, always shaping itself intentionally. Peat critiques genetic determinism and instead points to the capacity of living systems to generate new forms and purposes in response to their environment.

This clashes head-on with Darwinian orthodoxy, which frames life as a reaction to random mutations and selective pressures. Peat leaned closer to a Lamarckian view: organisms change because they want to live better.4 Adaptation is intelligent and energetic, not blind and brutal. Modern epigenetics lends support to this view. We now know that environmental signals like diet, stress, or toxins can alter gene expression within a single lifetime, sometimes even passing effects to the next generation.5 Life, it seems, is more responsive, more purposeful, than the neo-Darwinian narrative allows. Peat’s teleology is not a return to mystical vitalism but a recognition of life’s inherent creativity. Organisms don’t just survive; they strive, not through sheer willpower but through the intelligence of their energy flows.

Matter’s Memory: Hysteresis and the Inheritance of Form

Mainstream science treats matter as passive, its atoms identical and without a past. Peat disagreed. Matter, he argued, holds a kind of memory, a history woven into its form and function. Nascent oxygen, for example, behaves differently than “older” oxygen. A magnet’s properties depend on its previous states. This is hysteresis: the dependence of a system not just on current inputs but on the path it took to get there.6 To Peat, this suggested that matter is not a blank slate. It has been written on. In this sense, the universe is more like a poem than a machine: a layered text, shaped by energy and intention over time.

Think of water in homeopathy, where it is claimed to retain the “memory” of substances it once contained, even after dilution. While controversial and very “woo” for many, this idea echoes Peat’s view of matter as historically sensitive. Or think of crystals, whose growth patterns reflect the conditions of their formation, each layer a record of past energy flows. Hysteresis isn’t just a quirk, it is a clue to the universe’s relational nature. Matter doesn’t forget; it integrates, carrying its history into the present.

Energy as the Medium of Meaning

If matter holds memory, then energy imparts meaning. For Ray Peat, energy was not merely brute force, it was a patterning principle. In living systems, energy is not simply used up; it organises, coordinates, and creates. Peat often cited the Russian geologist and geochemist, Vladimir Vernadsky, who in the 1930s observed that open systems far from equilibrium don’t collapse into chaos.7 On the contrary, they tend toward greater order—so long as energy flows through them. As Vernadsky wrote, “living organisms have never been produced by inert matter… living matter is always generated from life itself,” implying a self-perpetuating complexity at the heart of life.

Vernadsky’s insights anticipated what would later be formalised by Begian physical chemist Ilya Prigogine as dissipative structures—systems that maintain or increase order through the continuous dissipation of energy.8 This is the paradox of life: it sustains order by dancing on the edge of disorder. Like a whirlpool that holds its form not despite the water’s flow but because of it, life persists as a dynamic equilibrium, complexity born through flux. Where conventional thermodynamics sees entropy as king, Peat saw a world of syntropic potential: cells drawing nutrients into coherence, minds weaving memory into meaning, societies evolving through shared attention and exchange.9 Energy, in this view, is not just fuel, it is information, guiding matter toward greater possibility.10

Teleology vs. Competition: Rejecting Scarcity Myths

Peat’s teleological vision rejects some of the tired myths of modern life, ideas so ubiquitous we mistake them for common sense: “No pain, no gain,” “You have to earn a living,” “Survival of the fittest.” These are not truths about nature, they are ideological leftovers from an era that confused stress with strength, and trauma with growth. Peat knew this well. His entire philosophy was built on the premise that living systems flourish under abundance, not adversity. Growth comes from sufficient energy, not heroic suffering. In this, Peat echoed a sentiment often attributed to the American systems theorist and futurist, Buckminster Fuller, who he admired: “Never again will what one does creatively, productively, and unselfishly be equated with earning a living.” While the exact source is unclear, Fuller similarly argued that, “we must do away with the absolutely specious notion that everybody has to earn a living,” envisioning a world where technology frees us to create without drudgery.11

For both thinkers, the idea that life must be justified through toil was a failure of imagination, and of metaphysics. Scarcity, in Peat’s view, is not a fact of life but a pathological condition: biological, cultural, and economic. When systems lack energy, they grow rigid, competitive, authoritarian, hierarchical. When energy flows, cooperation becomes natural. The body collaborates with itself; people collaborate with each other. Consider modern economies: obsessed with productivity, they glorify struggle and ignore the metabolic costs of stress. Yet, as Peat might argue, true wealth—biological or social—comes from energy surplus, not scarcity-driven competition. A society with abundant energy fosters creativity, not conflict.12

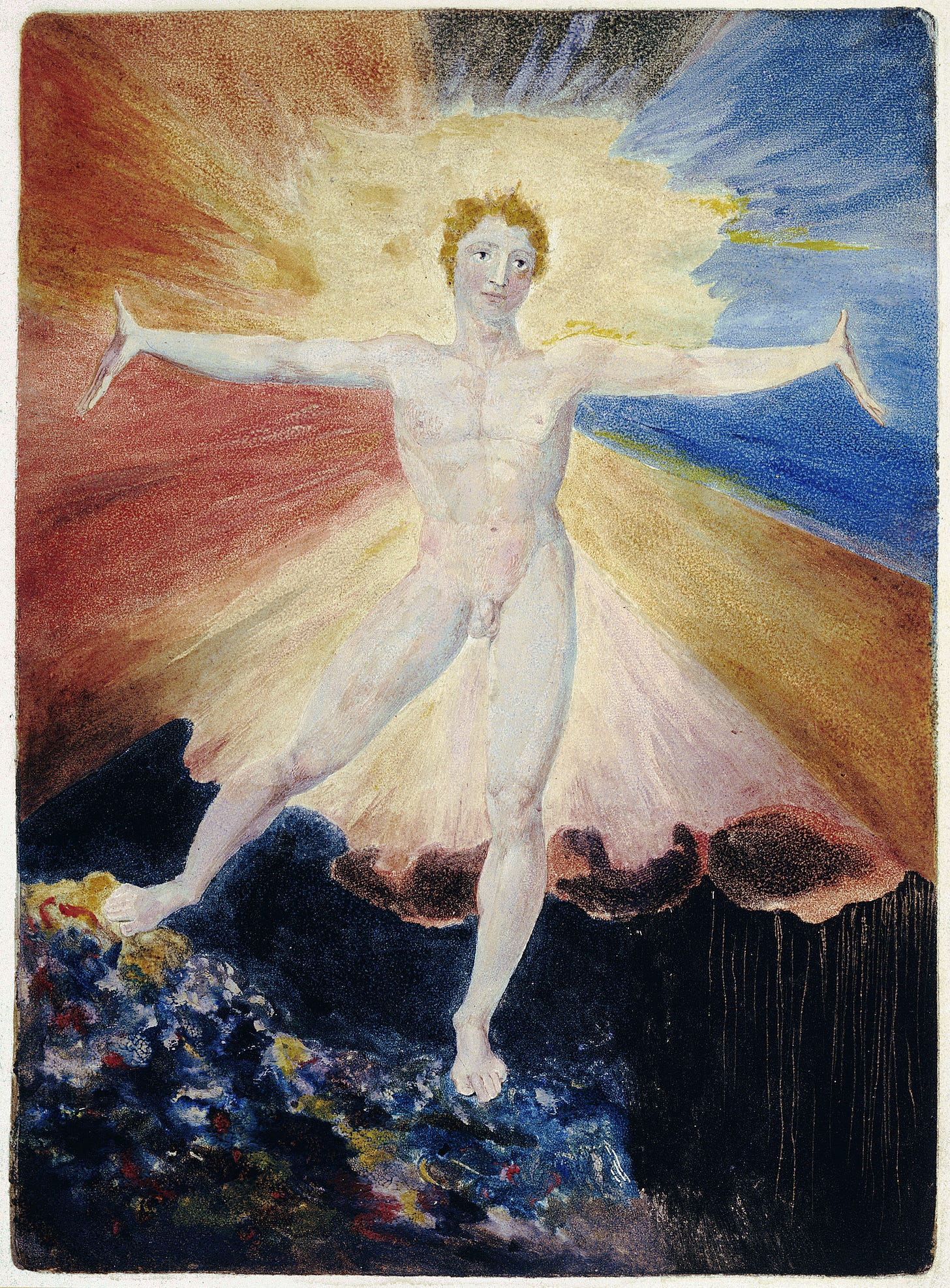

Blake’s Intellectual Fountain

Peat also drew deeply from William Blake, the great English poet and painter. His “intellectual fountain” offered a perspective distinct from Schopenhauer and Nietzsche’s idea of “Will” (or assertion) as the fundamental reality. For Peat and Blake, assertion can overshadow perception. A traumatised organism, in their view, doesn’t just shut down; it becomes rigid, moralistic, controlling. Peat writes: “When the organism is traumatised, it hardens, and stops developing, and wants to impose its moral hardness everywhere; assertiveness is the antithesis of perceptive life.”13 This is not merely psychology, it is metaphysics. Life, in Peat’s eyes, is about discovery, not dominance. To be alive is to be permeable, not armoured; adaptive, not aggressive; curious, not certain. The goal is not to impose order on a hostile world, but to join its creative unfolding. Blake’s line, “Energy is Eternal Delight,” captures this perfectly. For both thinkers, vitality is not a power struggle but a celebration of possibility. Life, when fuelled by energy, becomes art, a dance of creation, not a battle for survival.

From Physiology to Philosophy: A Life-Affirming Cosmology

Peat’s work is often misunderstood as niche biochemistry or fringe nutrition advice, especially in an age of social media and online health influencers, but that misses the bigger picture. Beneath the surface is a deep, coherent worldview, one that reframes life not as a fight against decay, but as a cosmic improvisation of energy and form. He offers us a subtle yet subversive take on the deepest human questions: why we suffer, what health really is, how we ought to live. His answer, stripped to its essence, is this: life becomes what it has the energy to perceive, feel, and create. The more energy we have, the more possibility we can hold. Suffering, in this view, is often a sign of blocked energy, whether in cells, minds, or societies. Health is the free flow of energy, enabling adaptation and growth. And how we live? By aligning with life’s creative impulse, not resisting it.

Peat didn’t offer us a rulebook, he gave us a way of seeing. A philosophy of aliveness. One that invites us to stay with the contradictions, to hold both heat and cool, structure and flow, logic and instinct. To live not as mechanical beings in a closed loop, but as creative agents in an open system: attuned, adaptive, alive. His work reminds us, life is not a static puzzle to be solved but a dynamic balance to be lived. While the left hemisphere reduces life to parts and systems, Peat and McGilchrist both remind us that life is not a machine. It is a breathing cosmos of interactions, responsive to light, to rhythm, to meaning. Peat chose the poetic. The experimental. The human.

What Peat Leaves Us With: “Perceive. Think. Act.”

Perceive. Begin with attention. Not filtered through ideology or fear, but clear, direct seeing. Let the body and world speak, and learn to listen. Perception, not control, is the beginning of wisdom.

Think. Not in pre-approved paradigms, but with freshness. Resist the seduction of false certainty. Let thought be lively, relational, and open-ended. Not a cage, but a lens.

Act. Not reactively, not from habit, but with creative agency. Informed by what you’ve seen and thought, take action that supports life, in you, in others, in the systems you touch.

This is not a catchy slogan. It is a practice. A rhythm. A way of being in the world. Peat doesn’t leave us with dogma. He leaves us with a direction: toward more life, toward coherence, toward the freedom to respond.

In terms of living it, nutrition can be a fundamental aspect, to which I may return. Just know that, for Peat, “Keeping the metabolic rate up is the main thing, and there are lots of ways to do it.”14

Two of Ray Peat’s books that are well worth reading:

Generative Energy explores biological energy as key to health, aging, and vitality.15 Blending science and philosophy, Peat challenges conventional views, linking metabolism to hormones, stress, and disease. He advocates a holistic approach to nutrition, emphasising thyroid function, progesterone, and ecological restoration to enhance longevity and creativity.

A slighty heavier read, Mind and Tissue is an exploration of Soviet neuroscientific research, emphasising the brain’s dynamic, energy-driven nature.16 Peat synthesises Russian studies on consciousness, perception, and brain function, challenging Western mechanistic models. He highlights how energy metabolism, hormones, and environmental factors shape mental processes, creativity, and health, advocating a holistic view of the mind as inseparable from the body’s biological vitality.

Iain Mcgilchrist is a psychiatrist, neuroscience researcher, philosopher and literary scholar, who wrote the excellent The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World (2009) and The Matter with Things: Our Brains, Our Delusions and the Unmaking of the World (2021).

Aristotle’s causa formalis or “formal cause” is is not merely a passive blueprint; it is an active, organising principle. In modern terms, it is sometimes compared to “information” or “active form” that determines the hierarchical organisation and emergent properties of complex systems, such as living organisms.

Alfred North Whitehead’s process philosophy argues that, “there is urgency in coming to see the world as a web of interrelated processes of which we are integral parts, so that all of our choices and actions have consequences for the world around us.”

Lamarckism, also known as Lamarckian inheritance or neo-Lamarckism, is the notion that an organism can pass on to its offspring physical characteristics that the parent organism acquired through use or disuse during its lifetime.

Hysteresis is the dependence of the state of a system on its history.

Vernadsky observed that Earth’s atmosphere and oceans are chemically unstable, with reactive gases like oxygen and methane coexisting in proportions that defy equilibrium expectations. This disequilibrium is sustained by living organisms, which actively transform energy and matter.

Ilya Prigogine was awarded the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1977 for his work on the thermodynamics of non-equilibrium systems. An interview with Ilya Prigogine.

See my last post, Syntropy and the Cosmic Seesaw

The New York Magazine Environmental Teach-in, New York Magazine (30 Mar, 1970).

The Philosophy of Ray Peat, Hermitix Podcast (YouTube).

Negation by Ray Peat (2014)

A useful start point for most people is the 2015 book “How to Heal Your Metabolism” by Kate Deering, as well as articles from Ray Peat himself at raypeat.com.

Generative Energy: Restoring The Wholeness Of Life (1994), read via The Internet Archive

Mind And Tissue: Russian Research Perspectives on the Human Brain (1976), read via The Internet Archive

An interesting read, thought provoking and the ideas resonate with me.

Your correlation of scientists looking at components rather than whole entities with McGilchrist’s divided brain approach is eminently understandable and quite masterful. Well done.